The concept of cybersquatting has already undergone a transformation journey from its origins in Web 1.0 to its current iteration in the era of Web3. As if cybercriminals had little to no choice but to penetrate the blockchain.

Both international and local regulations are still struggling to catch up with the rapid changes surrounding Web3. On one hand, blockchain users are grappling with new challenges facing their digital assets, and on the other hand, criminals are taking night shifts to devise new methods of “reaping where they didn’t sow”

Cybersquatters have historically registered well-known companies or brand names as internet domains. This maneuver has served not only as a means to derive financial benefits through resale but also as an instrument of fraud. The emergence of Web3, the third generation of the internet built on blockchain technology, is poised to witness a resurgence of similar conduct, now perpetrated by what is coined as ‘crypto squatters.

The motive behind both cybersquatting and cryptosquatting has been to hijack popular brand names and use them to deceive unsuspecting users. Sometimes directing traffic from a legitimate website to a fraudster’s website. Even where a brand does not have a reason to register a domain immediately, they find themselves having to make these registrations to protect themselves against Cybersquatting or Cybersquatting 2.0.

When Microsoft Sued a Teenager

One of the most famous cases of cybersquatting was that of Microsoft against teenager Mike Rowe. Mike, a high school student then, created a software business and called his domain name, mikerowesoft.com. This gesture did not sit well with Microsoft, thereby resulting in Mike being sued by the tech giant. However, Microsoft would go on to issue a $10 settlement to the teenager following a public backlash from the media and public.

A $10 settlement did not sit well with Mike too who asked Microsoft to purchase the domain name for $10,000. The response was an overwhelming 25-page cease-and-desist notice from the tech giant against the high school student.

This caused even more uproar from the public and the media, resulting in a settlement outside court between both parties. To date, mikerowesoft.com redirects to the official Microsoft.com. While this is not a classic example of criminal cybersquatting, it highlights the extent to which an established company would go to protect its brand name on the internet.

Nevertheless, the internet has witnessed even more grievous cybersquatting incidents like U.S. President Barack Obama’s re-election campaign dubbed Organising for Action. Just when the president announced they would turn the remaining campaign funds into a nonprofit, swindlers claimed the organisingforaction.com and organisingforaction.org domains. This was in 2012.

Web3 and the Evolution of Cybersquatting: Cybersquatting 2.0

Web3, which has emerged recently, relies on domains that serve as a memorable set of characters or substitutes for crypto wallet numbers. With domain extensions like .crypto, .eth, .nft, and .solana, Web3 simplifies cryptocurrency transfers, replacing the cumbersome 42-character crypto wallet numbers with more user-friendly domain names.

This evolution, however, brings with it the risk of crypto squatting, necessitating a proactive approach to protect brands and IP in this dynamic digital landscape.

Cybersquatting 2.0 is not necessarily a mere extension of the last decades’ cybersquatting but represents a paradigm shift in internet-driven fraud practices. If left to continue evolving, Cybersquatting 2.0 or Cryptosquatting poses even more severe risks than its predecessor due to the decentralized and anonymous nature of the blockchain.

Cybersquatting 2.0 does not only target Web3 domains but also Non-Fungible Tokens. Cryptosquatters, armed with a keen understanding of the decentralized ecosystem, exploit vulnerabilities in Web3 domains for their illicit gains. On the other hand, fraudulent actors may register on NFT marketplaces like OpenSea and pose as prominent figures to create demand for fake collections.

To comprehend the gravity of the situation, here are some examples of Cybersquatting 2.0:

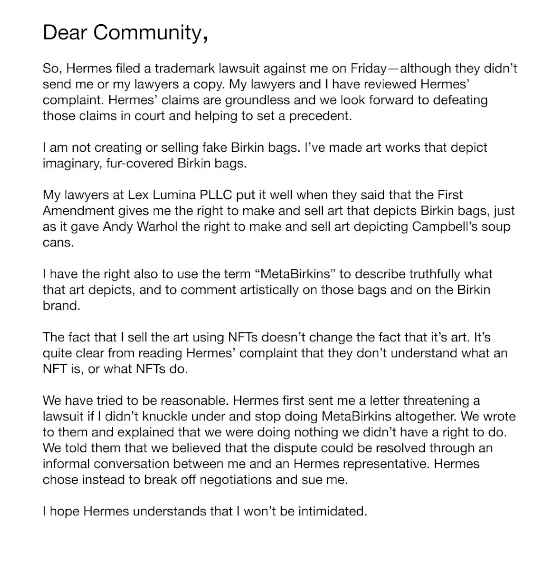

The Meta Birkins NFTs Collection

Hermes, a luxury fashion brand for bags and women’s apparel discovered that someone had made hundreds of thousands of dollars by generating an NFT collection out of Hermès bags.

The collection dubbed Meta Birkins NFTs prototyped tons of images from Hermès bags to create the NFTs. When Hermès discovered this, the fashion apparel company filed a lawsuit against Hermes in a U.S. court.

Copycatting NFTs and impersonating prominent names to create collectible fakes are good examples of Cybersquatting in the age of Web3.

Impersonation or phishing schemes by impersonating Decentralized Apps (dApps) is another practice that has gained prominence in DEFI Cybersquatting. Bad actors register Web3 domains resembling popular dApps, tricking users into interacting with malicious platforms. This tactic compromises user data, and private keys, and undermines the integrity of genuine decentralized applications.

An infamous example is the Inferno Drainer which saw the alleged business steal over $5.95 million from approximately 5,000 victims. According to sources, the scammers behind the attacks created hundreds of domain names targeting big DEFI brands like Metamask, Pepe, Collab.Land, Pancakeswap, Opensea, and LayerZero.

Wallstreet Memes Fakes

A more recent case happened to the Wallstreetmemes project, a Web3 gaming and casino platform whose domain name is https://wallstmemes.com/

Upon launching their presale and the eventual listing of their token, $WSM, the project’s team noted an increase in domains resembling their official name. One such fake domain was wstmemes.live

Historically, Cybersquatters in Web 2.0 would create fake domain names like the one above to also sabotage brand names and compel companies into paying ransoms. For instance, a criminal could easily go for the CocaColaorg.IO and use the domain name to sabotage traffic from the official brand website. Sometimes even using the domain name to conduct illegal business at the expense of the trademark’s owner.

Legislations Against Cybersquatting 2.0

This resulted in two pieces of regulatory bills, the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) and the Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) of 1999.

UDRP gave registered trademark holders the right to obtain a transfer or enjoin a domain that used their trademark. Even if that trademark caused confusion like in the Microsoft Against Mike Rowa case. On the other hand, ACPA stated it would prevent cybersquatters from registering internet domain names that resembled trademarks.

To some extent, these enactments solved the cybersquatting problem in Web2 but not completely. However, just like back in the 90s, Cybersquatters have been actively gobbling up .eth domain names that contain popular trademarks. A good example to illustrate this situation is seeing Amazon.eth or Nike.eth on Opensea for anyone willing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars. One particular person did sell Adele.eth for $6,000.

Unlike DNS domains from back then, ENS domains like Adele.eth are decentralized and run on the Ethereum blockchain. Besides, the domains with an ETH extension are outside ICANN’s UDRP laws and are impossible to claim back.

As such, what should one do in case they find someone infringing intellectual property laws and sign up their trademark on the Ethereum ENS domain naming system?

Notify the platform in case the trademark is listed on marketplaces like Rarible or OpenSea. While all of these platforms have ways to deal with intellectual property violations, they all have different approaches. Hence, check out their terms and conditions page to be on the informed side. Once you notify the platform, the platform delists the name from its platform and notifies the owner of the delisting.